Journal of

Asian Martial Arts

|

|

| Volume 2 - Number 2 -

1993 |

INCREASED LUNG CAPACITY THROUGH

QIGONG BREATHING

TECHNIQUES OF CHUNG MOO DOE

BY PATRICK B. MASSEY, M.D., Ph.D., EUGENE THORNER, M.D. WILLIAM L. PRESTON, M.D.

& JOHN S. LEE, M.D.

Introduction

There are many reports of the healthful benefits of martial art training

(Zhao, 1984; Maliszewski 1992). Usually these reports consist of martial art

experts, as well as students, attesting to the value of their training programs.

These benefits can include improved physical fitness, resolution of specific

body problems and a subjective feeling of mental improvement. However, objective

evidence on the effectiveness of martial art training for improving the health

of the average student is lacking.

Martial art training involves the performance of specific movements over a

period of time until a certain proficiency is achieved. One important aspect of

many advanced martial art training programs involves the development of some

form of breathing control. Specific breathing forms (qigong) have been

alleged to improve the circulation and strengthen both the immune system and the

internal organs. Other qigong breathing forms stretch the muscles, clear

the mind and reduce stress (Eisenberg, 1985; Wilhelm, 1985). Qigong means

the practice of developing qi. Qi has been described as the energy

of the body. It is associated with breathing as well as muscle and mental

activity. It is more of a life energy than a measurable substance (Ming-Dao,

1990). Qigong breathing techniques are taught in the Chung Moo style of

martial art. Chung (mind) Moo (body) martial art (also known as Um Yang martial

arts) has its foundation in Chinese martial arts. It was first introduced into

the United States twenty years ago.

Our own positive experiences practicing qigong breathing (a cumulative

experience of twenty- nine years in the Chung Moo style of martial art) led us

to interview many other students who also practice qigong breathing

forms. They stated that they felt "energized" after practicing qigong

breathing and they were able to complete daily activities more easily. Many

stated that they had fewer colds, more energy and greater endurance. Some of

these students originally had been severe, activity-restricted asthmatics. After

practicing qigong breathing, they became very active and also noticed a

marked decrease in the use of their asthma medications (Massey and Thorner,

1992). We wanted to determine if there was a measurable, physiologic parameter

that could justify the apparent feeling of improved health in those practicing

qigong breathing. Since the students were practicing a specific breathing

form, the most obvious parameter to measure was the amount of air each student

could exhale with a single breath. We postulated that, through qigong

breathing techniques, there may be a significant increase in the lung capacity.

We compared the functional lung capacity in those students who practiced

qigong breathing with the lung capacities of an age- and height-matched

control population (national average). Our data confirmed that students who

practiced qigong breathing had a marked increase in their lung capacity.

METHODS

One hundred students training in the Chung Moo style of martial art

volunteered to participate in this study. Students were randomly selected and

represent an age span of between twenty and seventy-one years of age. All had

been practicing qigong breathing forms for at least four months.

The lung capacity of each student was measured using an Assess Peak Flow

Spirometer. Students, after taking a deep breath, would expel as much air as

possible, as fast as possible into the spirometer. The flow of air (liter/min.)

was measured by the spirometer. Spirometry was performed four consecutive times

per student. All students were evaluated before practicing qigong

breathing forms. The numeric value for each student was determined as the

average of the four attempts. The numeric value of each age group was an average

of all of the students in that age group.

The numeric value of lung capacity was calculated by using the national

standards for lung capacity and peak air flow volumes. Since lung capacity is

directly related to both age and height, student’s lung capacities were compared

with national averages for both their age and height (Leiner et al., 1963).

RESULTS

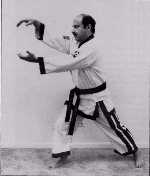

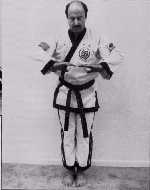

| A Sample Qigong Breathing

Technique |

| Photos courtesy of E. Thorner |

Figure I-1

Air is drawn into the lungs through the

nose as the arms and leg move to one side in unison. |

|

Figure I-2

Intake of air is completed as the arms

reach the level of the shoulders. The air is then pushed into the abdomen,

ready for expulsion. |

|

Figure I-3

Air is released in a controlled manner

as the arms move downward. |

|

Figure I-4

The movement is completed with total

release of the air, an extension of the arms toward the toes and a pulling

in of the stomach. *The entire sequence can then be

repeated. |

|

Figure I: Qigong breathing practiced by students in the Chung Moo

style of martial art. One of many different qigong breathing forms is

demonstrated. Air is taken in through the nose (Figs. I-1 and 2), forced down

into the abdominal area (Figs. I-3) and finally expelled through the mouth while

contracting the abdomen (Figs. I-3 and 4). These and other similar breathing

movements are practiced for twenty minutes per day, three to four times a week.

Movements are done in a relaxed manner and are continuous. Qigong

breathing movements are done an equal number of times on the right and left

side.

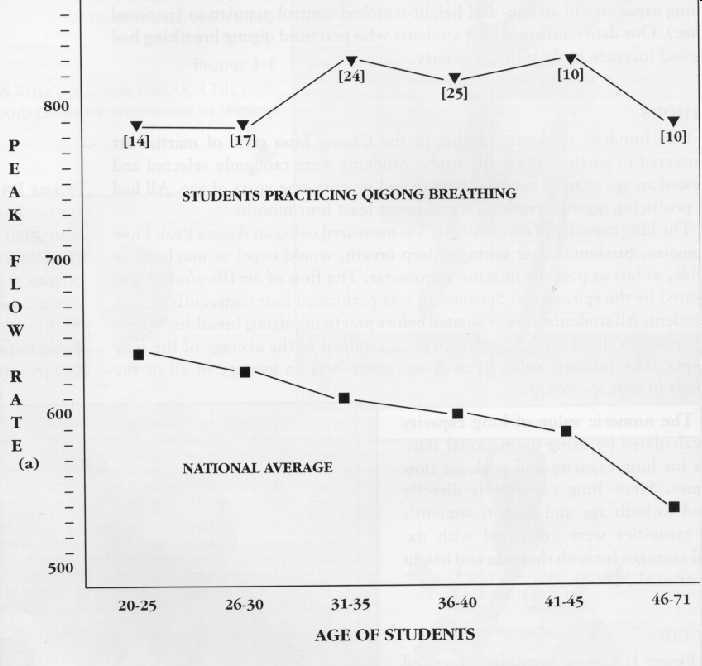

INCREASED PEAK FLOW RATE

IN STUDENTS PRACTICING QIGONG

BREATHING

IN THE CHUNG MOO-STYLE OF MARTIAL ART |

|

(a) Liters of air per minute

[] Number of students per

group |

Figure II: Increased peak flow rate in students practicing qigong

breathing in the Chung Moo Style of martial art. The peak flow for each age

group represents the maximum speed at which air was expelled from the lungs

after a single deep breath. Each value is the average of four measurements for

each student in the specific age group. These values were compared to the

national average for each age group. The national average peak air flow declines

with increasing age. In comparison, there was no decline in the peak air flow

for those students between the ages of twenty and seventy-one who practiced

qigong breathing.

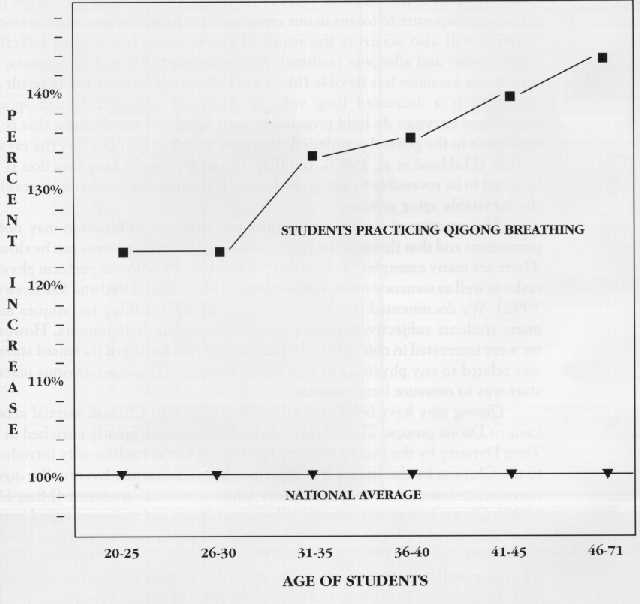

PERCENT INCREASE IN LUNG CAPACITY

OF STUDENTS

PRACTICING QIGONG BREATHING

IN THE CHUNG MOO-STYLE OF MARTIAL ART |

|

Figure III: Percent increase in the lung capacity of students practicing

qigong breathing in the Chung Moo martial art style. These data show that

the greatest percent increase in lung capacity is in the older students (between

thirty-six and seventy-one years of age) who practiced qigong breathing.

For comparison purposes, the national average lung capacity for each age group

was set at 100%. As a result, in the older students, the lung capacities were

30-45% greater than age- and height-matched controls (national average). A

smaller but significant increase over the national average (20-25%) was seen in

the younger students.

DISCUSSION

As the human body ages, certain functions diminish. There is a decrease in

hearing, eyesight, muscle mass, bone density, memory and learning. Reaction time

dramatically increases. There is also a decrease in lung capacity that is

believed to be irreversible (Poppy, 1992). This loss of lung capacity may

reflect structural chances of the chest shape resulting from increased curvature

of the spine and a loss of postural height ( most commonly the result of

osteoporosis). There are also changes in the lung tissue itself. The lung tissue

loses some of its elasticity. This is the result of years of scarring by

multiple insults to the lung tissue, e.g., exposure to toxins in our

environment: pollution and tobacco smoke. Scarring will also occur as the result

of the immune response to infections (pneumonia) and allergens (asthma). As the

amount of scarring increases, the lung tissue becomes less flexible (like a dry

balloon). The measurable result of a stiff lung is a decreased lung volume.

Although antioxidants and specific aerosolized enzymes do hold promise in some

specific lung diseases, this is not applicable to the general population; there

are no drugs that can stay the ravages of time (Hubbard et al. 1989). In other

words, the loss of lung function is not believed to be reversible to any great

degree. It is simply an unfortunate result of the inevitable aging process.

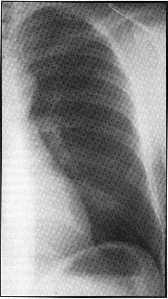

|

|

| A thirty year old male. |

A seventy-six year old male. |

X-Rays comparing the left lung

of a

young adult male with that of an elderly male.

The reduction of

lung capacity

is largely due to the effects of ageing.

However, this

common tendency for the

lungs to progressively decrease in

function

can be beneficially impeded by regular

practice of qigong

breathing exercises. |

The practice of martial arts emphasizes that loss of function may not be

permanent and that through the proper training, the aging process can be slowed.

There are many examples of older martial art students who can perform physical

tasks as well as someone many years younger (Ming-Dao, 1990 and Maliszewski,

1992). We documented that the practice of qigong breathing techniques

made many students subjectively more energetic, increased their stamina. However

we were interested in objectively documenting if this feeling of increased

stamina was related to any physical changes in the students. The most obvious

place to start was to measure lung capacity.

Qigong may have been originally introduced into Chinese martial arts

by various Daoist groups. These breathing techniques were greatly enriched in

the Tan Dynasty by the incorporation of breathing forms traditionally introduced

to the Chinese by the Indian Buddhist monk Bohidharma. Eventually, qigong

movements found their way into many Chinese martial art forms (Ming-Dao, 1990).

Qigong incorporates many different positions and movements and is most

often associated with promotion of health through the development of internal

strength (Chang, 1978). These breathing techniques are so intertwined with

Chinese martial arts that now it is almost impossible to practice advanced

martial art forms without being introduced to some form of qigong

breathing.

We wanted to evaluate the effects of qigong breathing on the lung

capacity. We needed a large group of participants who were all practicing the

same set of breathing movements. In this way the individual results from each

age group could be combined. We chose to evaluate students practicing the Chung

Moo style of martial art. The Chung Moo style has deep roots in Chinese martial

arts and specific qigong breathing forms are part of the training

program. Chung means a "balanced mind" and Moo means a "strong body." Chung Moo,

a name used generally throughout Asia, can also represent the aspects of Yin and

Yang (Chinese) or Um Yang (Korean), signifying a balance between the mind and

the body.

Practice of the qigong breathing movements involves a controlled

intake of a large volume of air into the lungs. The air is then pushed into the

abdominal area and then is followed by a controlled expelling of the air (Fig.

I). Our data confirmed the hypothesis that there was a measurable improvement in

lung capacity related to the subjective feeling of improved stamina in those

students practicing qigong breathing techniques. The older students

apparently realized the greatest benefit. Their resultant lung capacities were

much greater than their age- and height-matched controls (Fig. III). This may

reflect that an older student initially has a smaller lung capacity than a

younger student. Between the age of twenty and seventy-one, in the general

population, there is a loss of at least 30-35% of the lung capacity, the

equivalent of having one-third of the total lung mass surgically removed (West,

1977). However, this "lost" capacity is apparently not lost forever. After they

practiced qigong breathing techniques, the lung capacity of the older and

younger students were not statistically different (Fig. II). Interestingly, even

the younger students demonstrated a significant increase in lung capacity. This

indicates that there is considerable room for improvement even in the younger

student.

Unlike a machine, in the human body, specific organs, joints and tissues

become more efficient, more flexible or more supple with increased use (in the

right manner). Qigong breathing promotes a remarkable increase in the

lung capacity. Whether the increase in lung capacity reflects an increase in the

chest wall size or an increase in flexibility of the lung tissue itself can not

be determined from this study. One intriguing possibility is that qigong

breathing may train the student to tap into this large lung volume (West, 1977).

A whale, however, can exchange greater than 90% of its total lung volume.

Qigong breathing may train the student to tap into this large lung volume

reserve with every breath, to become more efficient in breathing. Again, this

study cannot answer this hypothesis.

As with all scientific studies, more questions are raised than answered.

Would breathing forms in other martial art styles compare favorably with those

taught in the Chung Moo style martial art? How fast do qigong breathing

techniques increase lung volume? Could qigong breathing movements reverse

the severe lung damage from emphysema and cystic fibrosis? How long do the

benefits last after stopping qigong breathing? What other organ systems

does qigong breathing affect? Preliminary blood pressure studies on

students practicing qigong breathing indicate that circulation is also

favorably influenced (data not published). It is clear that martial art training

and the study of medicine both seek answers to the same questions to understand

how the human body works. The combination of martial arts and medicine is

exciting in that new insights into how the human body works may be found.

REFERENCES

- Cheng, Stephen T. (1978). The book of internal exercises. San

Francisco:Strawberry Hill.

- China Sports Magazine. (1985). The wonders of qigong: A Chinese

exercise for fitness, health, and longevity. Los Angeles: Wayfarer.

- Eisenberg, David. (1985). Encounters with qi: Exploring Chinese

medicine. New York: Norton.

- Hubbard, R., McElvaney, N., Sellars, S., Healy, J., Czerski, D., Crystal,

R. (1989). Recombinant DNA- produced alpha 1-antitrypsin administered by

aerosol augments lower respiratory tract anti-neutrophil elastase defenses in

individuals with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Journal of Clinical

Investigation, 84, 1349-54.

- Leiner, G. C., Abramowitz, S., Small, M., Stenby, V.,Lewis, W. (1963).

Expiratory peak flow rate. Standard values for normal subjects. Use as a

clinical test of ventilary function. American Review of Respiratory

Diseases, 8, 644-48.

- Maliszewski, Michael. (1992). Medical, healing and spiritual components of

Asian martial arts. Journal of Asian Martial Arts, 1 (2), 25-56.

- Massey, Patrick and Thorner, Eugene. (1992). Personal testimonials

gathered from students practicing the Chung Mo style of martial art.

- Ming-Dao, Deng. (1990). Scholar warrior: An introduction to the Tao in

everyday life. San Francisco: Harper and Row.

- Poppy, John. (1992). How old are you really? Health, 6(7),

45-56.

- West, John B. (1977). monary pathophysiology: The essentials.

Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

- Zhao, Dahong. The Chinese exercise book: From ancient and modern

China-Exercises for well-being and the treatment of illness. Point

Roberts, Washington: Hatley and Marks.

|